Glutting ourselves on misery

The problem with the true crime genre is that it’s rife with manufactured mystery so that its merchants of misery can wring a few bucks from tragedy. When we comb through witness statements and freeze-frame interviews, we aren’t treating the loss of life with respect. Instead, we are reducing murder to an intellectual puzzle at best and tasteless entertainment at worst. Perhaps we consumers of misery ought to be ashamed too.

The thing about violent crime is that it’s all so sad and predictable it fails to be scintillating on its own. That’s why misdirection, red herrings and clever storytelling techniques are required to plant doubt in the viewers (I should say, voyeurs) until they’re in a tailspin, wondering whether wives have been gouged by owls or husbands fed to tigers.

A few years ago, it seemed everyone was swept up in the cultural phenomenon that was the Serial podcast. The hosts vacillated between dramatic and wisecracking; they knew how to keep us on tenterhooks the whole way through. I’d get chills when the staccato theme music played, capped off by a message informing us the call we were about to hear was from “an inmate at a Maryland correctional facility”. The best part of the Serial experience was swapping conjecture and floating pet theory to friends (“Oh, is that what you think, just wait till you get to Episode 3!”). We were all desperate to plumb depths that did not exist, ravenous for a plot twist that never came.

Spoiler: the ex-boyfriend did it, the one being interviewed from jail. What irks me is that even after all this time, I can still remember his name, but while listening to the podcast, I’d periodically forget the victim’s. Strange how the person at the heart of a true crime story is both catalyst and afterthought, about as fleshed out as a chalk outline. (What can I say? We prefer an active protagonist over a character who appears only in flashbacks.)

A woman is found dead at the bottom of The Staircase (cue dramatic music), spawning a popular Netflix documentary. Was it merely an unfortunate slip down the stairs, as her husband claims? The prosecution argues her husband bludgeoned her to death after discovering his gay affairs, then threw her down the stairs to fake an accident so that he and his son from another marriage could keep living the life to which they were accustomed.

The defence asserts it was a fatal drunken fall. Hang on, just like the fall that killed his female friend, whose daughters—the eldest strikingly resembling him—he adopted? Coincidence, inspiration, or is “Blame it on the staircase” this guy’s modus operandi? Unfortunately, the prosecution’s theory lacks allure; it’s too straightforward a narrative to satiate us. Much too simple for we who relish grand coincidences and revel in twists and turns.

Websleuths would prefer to think an owl flew in at that exact moment, lacerating the victim’s head and causing her to lose balance before flying away into the night and leaving behind neither fluff nor feather. But, unfortunately, the majority of murdered women are killed by their current or former male partners. (Men by their friends or associates.) What a depressing fact, and perhaps one of the reasons viewers were hoping for an alternative explanation: the staircase did it, an aggressive barn owl did it. Comedienne Michelle Wolf mercilessly skewers true crime documentaries of this sort in her bluntly titled parody The Husband Did It.

For me, true crime has worn out its welcome, and yet, I’m only human and find myself sucked in from time to time. The mind whirs away, late into the night. Obsessively, unhealthily, I pore over statement and body language analysis videos. I’m rewarded by spotting duping delight (a momentary quirking of the lip when the guilty party cannot suppress their joy for having fooled us all) or catching a Freudian slip in a decades-old interview. Oh, the witless public believed their PR campaign, but I know better. I am better. And although I can feel smug about knowing the truth behind the truth, ultimately, it doesn’t do anyone any good.

I lurk in forums where misquotations morph into popular theories, which branch off into many more right before my very eyes (“She was clutching an owl feather in her hand”). Two police sketches (“e-fits”) of the same suspect split him into a fictitious duo, doubling the intrigue. Oh, the frayed, messy, and heavily embellished rich tapestry of it all—one must resist becoming entangled in its many loose ends. But most of all, one must get on with one’s life rather than seethe in self-righteous indignation because they got away with it. And? What are you going to do about it? You’re merely indulging your morbid curiosity, and there’s nothing admirable about that, so let’s call a spade a spade (and “the murder weapon” if appropriate).

Of Monsters and Men

As a first-year psychology student, I found myself fascinated by psychopaths. To think, people wholly unburdened by a conscience walk among us, sometimes thriving as CEOs, lawyers, and surgeons, often sitting behind bars for crimes most heinous. However, psychopaths aren’t all that mysterious; they’re merely under-developed in the areas of the brain which comprise our empathy “circuit”. I’m not talking about a cerebral understanding of empathy or the ability to cleave to societal conventions where advantageous. I mean the visceral kind of empathy, the pain you cannot help but feel right down to your marrow when someone else is hurting.

I did not like what I learnt while researching psychopaths; it’s true what they caution about gazing into the abyss, that you grant it an aperture into the dark confines of your skull. Because here’s the genuinely scary part: empathy has an off-switch. Given the right circumstances, we can all be as callous as those we brand butchers. And we don’t even have to dehumanise the victim to do it; we merely have to convince ourselves that they deserved it.

Typically, when we imagine another person’s pain, it makes us think of our own, activating the anterior cingulate cortex and enabling us to empathise. However, brain scans show that when we feel a victim deserved their fate, the anterior cingulate cortex fails to light up, with this effect particularly pronounced in men. (Perhaps only while they’re young, as psychopathy tends to decline with age if I remember my uni lectures correctly.)

As long as we believe a punitive action is justified, we feel nothing for its recipient. Unfortunately, one can justify absolutely anything; it all boils down to semantics, framing, in-group versus out-group and, not forgetting, our penchant for self-serving mental gymnastics. Whether you’re gleeful that a child murderer will fry on the electric chair or scornful of a drunk “party girl” raped while unconscious and dressed in immodest clothes, this is the mechanism at work. From victim-blaming to mass murder in the millions, every atrocity is neither inexplicable nor inhuman.

That’s why I so disapprove of bombastic titles like ‘The Monster of Florence’ (Il Mostro di Firenze in the original Italian). Why elevate evil as though it were extraordinary and not of this world? Willful ignorance and denial will not help us conquer the darkness inherent in the human psyche; we must acknowledge evil’s true nature, its banality and abundance. Come to think of it, ‘The Banal, Violent and Impotent Man of Florence’ is a much better appellation for the appalling, with the added benefit of being unappealing to any would-be copycat killer courting infamy.

This particular pathetic man murdered amorous young couples parked for privacy in the Tuscan countryside because he felt inadequate and envious. And most importantly, he felt entitled to inflict his pain on others, rather than feeling their pain as his own and staying his hand. The devil’s the details, shall I describe them, the dates, facts and figures? But that would be antithetical to my thesis, for no case is remarkable for its gory details but for the fact that each is singularly and intensely tragic for its loss of life. The set-dressing or backdrop doesn’t matter — though what a lovely one it was:

The Monster of Florence by Douglas Preston is my favourite true crime book, but not for the banal and violent man at its epicentre. On the contrary, I prefer its periphery, filled with power-mad prosecutors, corrupt police, and a bloodthirsty public. The book investigates the “monster’s” true identity, for there were many patsies, and in doing so, opens an aperture onto our own unsavoury nature. The serial killer, responsible for at least fourteen violent deaths, was likely a blue-collar Sicilian gutting his victims with a scuba knife. (He brings up possession of the murder weapon casually, by the by, you know, and I know but prove it in a court of law to the author and his investigative journalist friend. What a braggart. What a lowlife.)

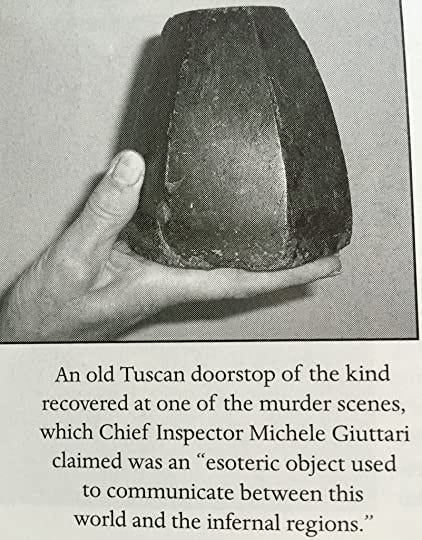

The Italian public found the man lacking, a bitter disappointment. They much preferred the legend, a monster of their own making: an upper-class doctor elegantly wielding a scalpel in the service of his shadowy masters and Satan himself. An “arcane relic” was even discovered at the crime scene, ‘an esoteric object used to communicate between this world and the infernal regions’. It turned out to be the victim’s doorstop (pictured below). To be fair, it does look a bit like a 3rd Generation Amazon Echo, which may, or may not, communicate all that you say in front of it to some rather infernal figures rather than the Cloud, so evocative of heaven.

The ‘Monster of Florence’ case gave birth to the iconic cannibal-killer Hannibal Lecter, a more palatable monster — pardon the pun — yet one as much the polar opposite of his inspiration as it’s possible to be. I suppose when it comes to literature and the silver screen, we want our villains a tad more glamorous than reality affords, with aristocratic airs, a silver tongue, and a mind like a steel trap. As though complex philosophies could account for or absolve brutality, make it any less contemptible. But it does make for a far more enthralling tale. That’s the trouble; we luxuriate in true crime as readily as we do in pulp fiction and cosy mysteries, as though real-life tragedies were also stories spun for our amusement.

Dietrologia and the Devil

Dietrologia: the obsessive search for supposedly hidden motives behind events or behind people’s actions and words.

In The Monster of Florence, Douglas Preston implicates ‘dietrologia’, sometimes translated into English as ‘behindology’, to explain the public’s craving for a juicier story. Dietrologia refers to the tendency to reject official explanations in favour of something more convoluted and, therefore, satisfying.

We seek the truth behind the truth so that we may be smug about it. No one wants to be the rube who accepts things at face value, only to find out something far murkier lay beneath the surface all along. By this reckoning, it’s better to be incorrigibly and deeply cynical than to be wrong. (Whereas every dyed-in-the-wool cynic laments they’re not wrong more often.)

Parting thoughts

We are vultures picking over evidence exculpatory, damning, and damn irrelevant. Not only are we merchants and consumers of misery, but we are much too enamoured with monsters and the Satanic. We want brutes to be bona fide monsters so that we may disqualify them from humanity and preserve our collective image. We feel the need to externalise evil as an otherworldly tempter possessing supernatural powers of influence to downplay our own agency. According to Voltaire, “If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him”.

Well, it looks like we invented the Devil too.

Please consider buyingmeacoffee or becoming a paid subscriber to help in my writing endeavours.